The celebrated British artist Sam Jackson on creating contemporary classicism

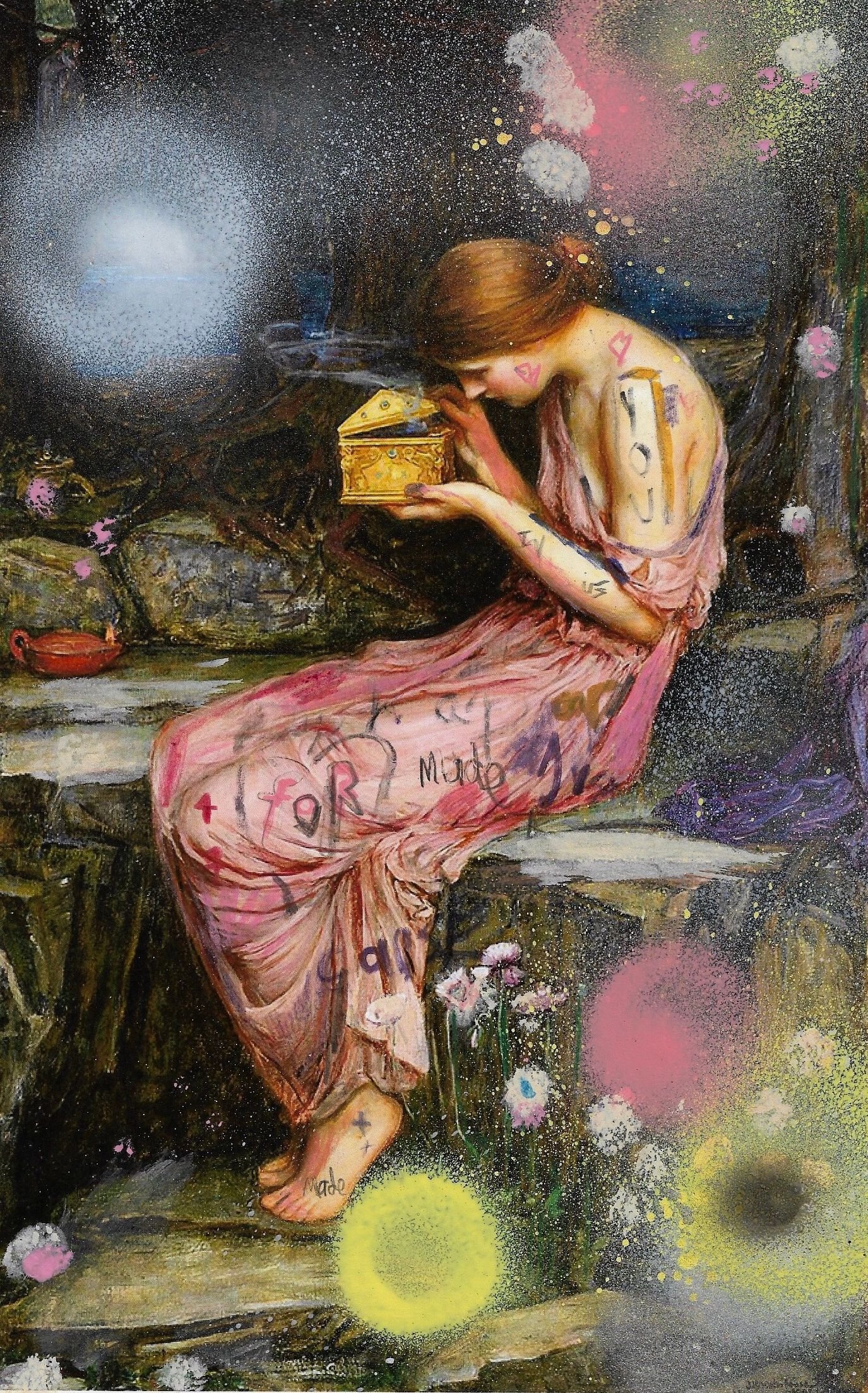

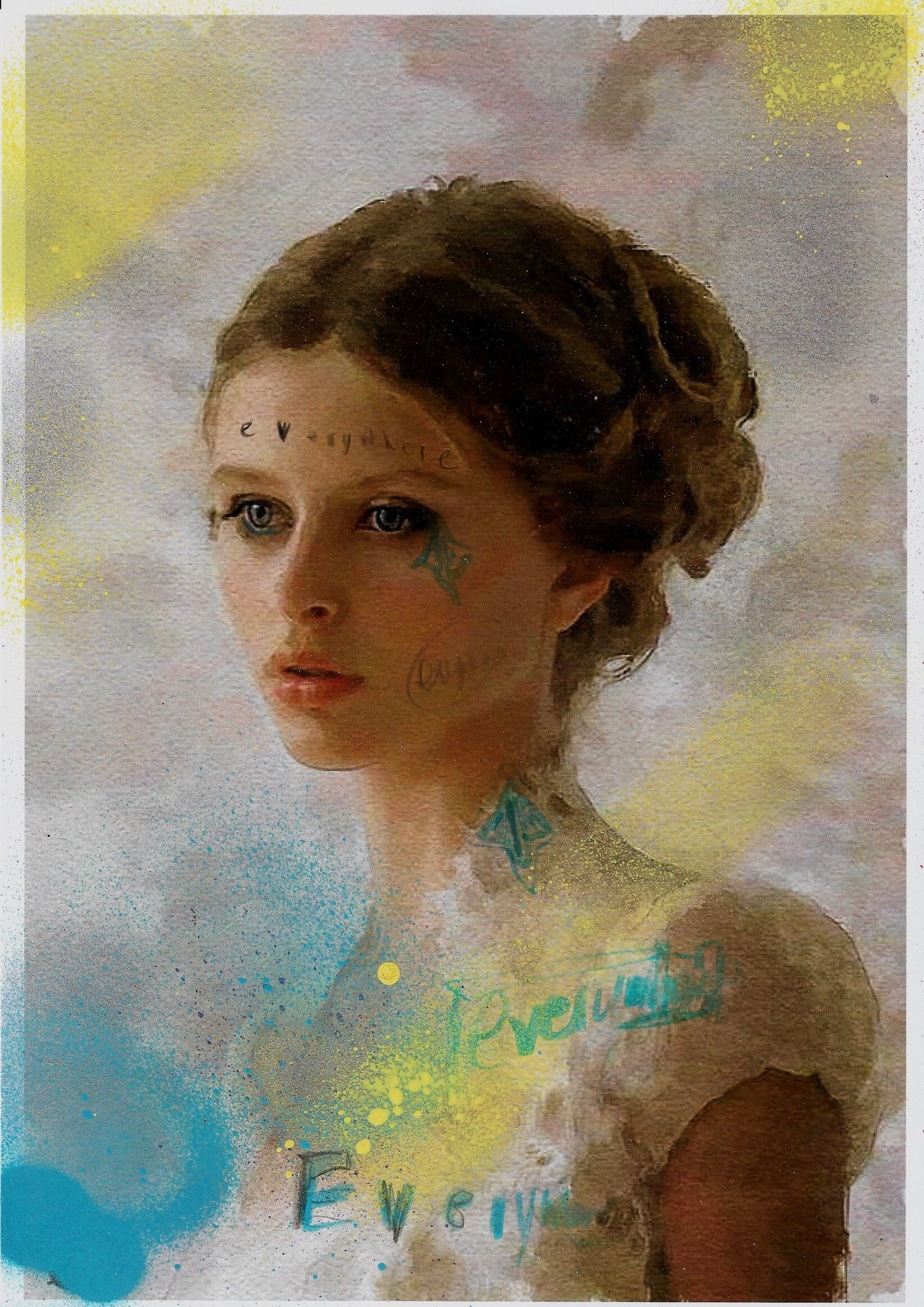

The British artist Sam Jackson has been trailblazing a modern approach to portraiture ever since his graduation from the Royal Academy back in 2007, and is currently on something of a transatlantic tour, following his recent mid-career retrospective. Over the course of a fifteen-year career Jackson has exhibited all over the world, and won considerable global acclaim, forwarding an aesthetic that effortlessly straddles classical painting, tagging, graffiti and the visual cultures of graphic and tattoo art. He then blends these various aesthetic disciplines with fragmented text that inveigles one into a dream-like reverie of being - the amalgamation of personal and societal motifs resulting in a symbolic fugue that taps into Jungian notions of collective consciousness. His appropriation of classical portraiture is particularly interesting in this regard, making us reconsider traditional notions of beauty amidst scattered scrawled words and blotches of spray-can paint – often fusing emotive biographical and autobiographical information in a heavily layered and defiant abstraction of clear meaning. In this rare interview, the artist talks to Cognizant about the nature of nostalgia, reaching for a commonality of human experience and forever seeking an intangible truth.

What would you say essentially drives you as an artist?

I’ve always been interested in the language of painting, and painting, of course, is always in a state of flux – it’s always in or out of vogue. When I was studying at the Royal Academy in the mid-noughties there was still quite an overhang of the YBA movement, and there was a very strong element of artists wanting to be controversial, to shock, or open up conversations around transgression or subversion. I loved The Chapmans and Sarah Lucas, but I was trying to find my own language within a painting context, and I was also discovering the literature of Bataille and De Sade, which had a profound effect on me, perhaps even more so. I was very driven by this idea of a kind of intensity linked in with a painterly language, and I suppose my goal was to try and bring an almost traditional language of painting into the contemporary.

How does nostalgia play out in your work, and how do you conceive of the role of nostalgia in art-making?

That is a fascinating question. I think when it comes to nostalgia people will often think of it as something that is linked to the past, or something that contains a romanticism, and I think there probably is some of that in my work, but I think nostalgia is present more as a seeking for a place or time that has never existed. I think that maybe there is a kind of longing in the work also for something that has never been fulfilled. There is definitely something in the paintings that tries to link into a transportive or transformative kind of process, so that you can be taken to something to ‘other’ – and that can be a universal other. The paintings are not just linked to my personal past, but more to something that we can all kind of connect with. The nostalgia that is in there acts as my navigation in a sense. In terms of referencing various histories – art history, personal history, print history, music history – these all allow me to move through nostalgia in a way that locates something for me. I suppose I am often using that to try to get to this idea of almost these core common elements of humanity – emotionally, politically, socially, sexually, et cetera.

Would you say that trying to tap into the commonality of human experience is something that is key to your practice?

I think there is definitely a commonality that maybe people can get from the work, regardless of their past, because from speaking to people that are very well educated and cultured, to people like the friends I grew up with, who have no idea about about painting, then they will still often say, there's something really cool about that painting, Sam. Maybe in that sense there is something close to a truth seeking that I am trying to bring forth in my work, but, hopefully, in a way that feels authentic and isn't overt. Actually, finding that line between presenting something that is authentic and is the real deal rather than something cheesy is a balancing act I've always found incredibly difficult. I'm very aesthetically very aware as an artist, and I've never really wanted to be pigeonholed as a Royal Academy painter, but neither have I wanted for my work to be seen as street art. I've always navigated that in the back of my mind, because I've always loved painters like Carrvaggio and Rembrandt and been interested in how they can relate to the contemporary. I've never been one of those artists that would purposely try to make something that is oppositional, or that I would class as ugly, even though it might be more challenging conceptually.

Given your love of classical art, how would you say notions of beauty play out in your work?

Well, I think I've always been very aware of beauty, even just in terms of being in bands when I was younger and being interested in clothes and fashion, and I think a strong understanding of aesthetics can come from that kind of immersion in style culture. There have always been questions of beauty apparent in making the work, even from very early critiques at The RA. And I suppose, for me, there is always a certain essence of beauty at work, which holds true whatever I paint. But expressing how that makes sense is quite difficult. Is it in an innocence? Is it in a mark? Is it in a certain colour? Is it in contrast? I think it's in all of that, but, as you say, there is also a classical idea of beauty that I very much appreciate. Even when it comes to the graphic and quite sexualised pieces I first became known for, I think there is an inherent beauty to them – there is always something in there, like a deconstructed idealised version of beauty, or a comment on the transience of youth. I do think beauty is intangible, and these commonalities and things that I'm interested in are complex, yet they are also paradoxically kind of simple. That is perhaps the beauty of art, to be able to communicate things that it wouldn’t be possible to express in any other way.

Do you have very specific intentions when facing a blank canvas? What do you think about the rise of generative digital art?

I have always felt that I’m just a conduit when making work – often people can look at a painting and get something from it that I had never consciously intended or seen, and I suppose that is the experiential element of the process that I enjoy most. There has always been a digital element to my painting, because from the get-go I was using the screen to find images – but, of course, back then it was just about using the internet to source imagery rather than utilising the possibilities of new platforms or technologies. It’s very different now. I’m a private person, and there is a real overtness in being open about everything on social media now, which, in terms of art-making, seems quite strange. I can't think of anything worse than to be putting work up on Instagram while it is in process, or while studying art. It must be a very odd experience to have that immediate judgement, and to be almost manoeuvred by the responses. It’s a different kind of mentality.

The British artist Sam Jackson has been trailblazing a modern approach to portraiture ever since his graduation from the Royal Academy back in 2007, and is currently on something of a transatlantic tour, following his recent mid-career retrospective. Over the course of a fifteen-year career Jackson has exhibited all over the world, and won considerable global acclaim, forwarding an aesthetic that effortlessly straddles classical painting, tagging, graffiti and the visual cultures of graphic and tattoo art. He then blends these various aesthetic disciplines with fragmented text that inveigles one into a dream-like reverie of being - the amalgamation of personal and societal motifs resulting in a symbolic fugue that taps into Jungian notions of collective consciousness. His appropriation of classical portraiture is particularly interesting in this regard, making us reconsider traditional notions of beauty amidst scattered scrawled words and blotches of spray-can paint – often fusing emotive biographical and autobiographical information in a heavily layered and defiant abstraction of clear meaning. In this rare interview, the artist talks to Cognizant about the nature of nostalgia, reaching for a commonality of human experience and forever seeking an intangible truth.

What would you say essentially drives you as an artist?

I’ve always been interested in the language of painting, and painting, of course, is always in a state of flux – it’s always in or out of vogue. When I was studying at the Royal Academy in the mid-noughties there was still quite an overhang of the YBA movement, and there was a very strong element of artists wanting to be controversial, to shock, or open up conversations around transgression or subversion. I loved The Chapmans and Sarah Lucas, but I was trying to find my own language within a painting context, and I was also discovering the literature of Bataille and De Sade, which had a profound effect on me, perhaps even more so. I was very driven by this idea of a kind of intensity linked in with a painterly language, and I suppose my goal was to try and bring an almost traditional language of painting into the contemporary.

How does nostalgia play out in your work, and how do you conceive of the role of nostalgia in art-making?

That is a fascinating question. I think when it comes to nostalgia people will often think of it as something that is linked to the past, or something that contains a romanticism, and I think there probably is some of that in my work, but I think nostalgia is present more as a seeking for a place or time that has never existed. I think that maybe there is a kind of longing in the work also for something that has never been fulfilled. There is definitely something in the paintings that tries to link into a transportive or transformative kind of process, so that you can be taken to something to ‘other’ – and that can be a universal other. The paintings are not just linked to my personal past, but more to something that we can all kind of connect with. The nostalgia that is in there acts as my navigation in a sense. In terms of referencing various histories – art history, personal history, print history, music history – these all allow me to move through nostalgia in a way that locates something for me. I suppose I am often using that to try to get to this idea of almost these core common elements of humanity – emotionally, politically, socially, sexually, et cetera.

Would you say that trying to tap into the commonality of human experience is something that is key to your practice?

I think there is definitely a commonality that maybe people can get from the work, regardless of their past, because from speaking to people that are very well educated and cultured, to people like the friends I grew up with, who have no idea about about painting, then they will still often say, there's something really cool about that painting, Sam. Maybe in that sense there is something close to a truth seeking that I am trying to bring forth in my work, but, hopefully, in a way that feels authentic and isn't overt. Actually, finding that line between presenting something that is authentic and is the real deal rather than something cheesy is a balancing act I've always found incredibly difficult. I'm very aesthetically very aware as an artist, and I've never really wanted to be pigeonholed as a Royal Academy painter, but neither have I wanted for my work to be seen as street art. I've always navigated that in the back of my mind, because I've always loved painters like Carrvaggio and Rembrandt and been interested in how they can relate to the contemporary. I've never been one of those artists that would purposely try to make something that is oppositional, or that I would class as ugly, even though it might be more challenging conceptually.

Given your love of classical art, how would you say notions of beauty play out in your work?

Well, I think I've always been very aware of beauty, even just in terms of being in bands when I was younger and being interested in clothes and fashion, and I think a strong understanding of aesthetics can come from that kind of immersion in style culture. There have always been questions of beauty apparent in making the work, even from very early critiques at The RA. And I suppose, for me, there is always a certain essence of beauty at work, which holds true whatever I paint. But expressing how that makes sense is quite difficult. Is it in an innocence? Is it in a mark? Is it in a certain colour? Is it in contrast? I think it's in all of that, but, as you say, there is also a classical idea of beauty that I very much appreciate. Even when it comes to the graphic and quite sexualised pieces I first became known for, I think there is an inherent beauty to them – there is always something in there, like a deconstructed idealised version of beauty, or a comment on the transience of youth. I do think beauty is intangible, and these commonalities and things that I'm interested in are complex, yet they are also paradoxically kind of simple. That is perhaps the beauty of art, to be able to communicate things that it wouldn’t be possible to express in any other way.

Do you have very specific intentions when facing a blank canvas? What do you think about the rise of generative digital art?

I have always felt that I’m just a conduit when making work – often people can look at a painting and get something from it that I had never consciously intended or seen, and I suppose that is the experiential element of the process that I enjoy most. There has always been a digital element to my painting, because from the get-go I was using the screen to find images – but, of course, back then it was just about using the internet to source imagery rather than utilising the possibilities of new platforms or technologies. It’s very different now. I’m a private person, and there is a real overtness in being open about everything on social media now, which, in terms of art-making, seems quite strange. I can't think of anything worse than to be putting work up on Instagram while it is in process, or while studying art. It must be a very odd experience to have that immediate judgement, and to be almost manoeuvred by the responses. It’s a different kind of mentality.

The British artist Sam Jackson has been trailblazing a modern approach to portraiture ever since his graduation from the Royal Academy back in 2007, and is currently on something of a transatlantic tour, following his recent mid-career retrospective. Over the course of a fifteen-year career Jackson has exhibited all over the world, and won considerable global acclaim, forwarding an aesthetic that effortlessly straddles classical painting, tagging, graffiti and the visual cultures of graphic and tattoo art. He then blends these various aesthetic disciplines with fragmented text that inveigles one into a dream-like reverie of being - the amalgamation of personal and societal motifs resulting in a symbolic fugue that taps into Jungian notions of collective consciousness. His appropriation of classical portraiture is particularly interesting in this regard, making us reconsider traditional notions of beauty amidst scattered scrawled words and blotches of spray-can paint – often fusing emotive biographical and autobiographical information in a heavily layered and defiant abstraction of clear meaning. In this rare interview, the artist talks to Cognizant about the nature of nostalgia, reaching for a commonality of human experience and forever seeking an intangible truth.

What would you say essentially drives you as an artist?

I’ve always been interested in the language of painting, and painting, of course, is always in a state of flux – it’s always in or out of vogue. When I was studying at the Royal Academy in the mid-noughties there was still quite an overhang of the YBA movement, and there was a very strong element of artists wanting to be controversial, to shock, or open up conversations around transgression or subversion. I loved The Chapmans and Sarah Lucas, but I was trying to find my own language within a painting context, and I was also discovering the literature of Bataille and De Sade, which had a profound effect on me, perhaps even more so. I was very driven by this idea of a kind of intensity linked in with a painterly language, and I suppose my goal was to try and bring an almost traditional language of painting into the contemporary.

How does nostalgia play out in your work, and how do you conceive of the role of nostalgia in art-making?

That is a fascinating question. I think when it comes to nostalgia people will often think of it as something that is linked to the past, or something that contains a romanticism, and I think there probably is some of that in my work, but I think nostalgia is present more as a seeking for a place or time that has never existed. I think that maybe there is a kind of longing in the work also for something that has never been fulfilled. There is definitely something in the paintings that tries to link into a transportive or transformative kind of process, so that you can be taken to something to ‘other’ – and that can be a universal other. The paintings are not just linked to my personal past, but more to something that we can all kind of connect with. The nostalgia that is in there acts as my navigation in a sense. In terms of referencing various histories – art history, personal history, print history, music history – these all allow me to move through nostalgia in a way that locates something for me. I suppose I am often using that to try to get to this idea of almost these core common elements of humanity – emotionally, politically, socially, sexually, et cetera.

Would you say that trying to tap into the commonality of human experience is something that is key to your practice?

I think there is definitely a commonality that maybe people can get from the work, regardless of their past, because from speaking to people that are very well educated and cultured, to people like the friends I grew up with, who have no idea about about painting, then they will still often say, there's something really cool about that painting, Sam. Maybe in that sense there is something close to a truth seeking that I am trying to bring forth in my work, but, hopefully, in a way that feels authentic and isn't overt. Actually, finding that line between presenting something that is authentic and is the real deal rather than something cheesy is a balancing act I've always found incredibly difficult. I'm very aesthetically very aware as an artist, and I've never really wanted to be pigeonholed as a Royal Academy painter, but neither have I wanted for my work to be seen as street art. I've always navigated that in the back of my mind, because I've always loved painters like Carrvaggio and Rembrandt and been interested in how they can relate to the contemporary. I've never been one of those artists that would purposely try to make something that is oppositional, or that I would class as ugly, even though it might be more challenging conceptually.

Given your love of classical art, how would you say notions of beauty play out in your work?

Well, I think I've always been very aware of beauty, even just in terms of being in bands when I was younger and being interested in clothes and fashion, and I think a strong understanding of aesthetics can come from that kind of immersion in style culture. There have always been questions of beauty apparent in making the work, even from very early critiques at The RA. And I suppose, for me, there is always a certain essence of beauty at work, which holds true whatever I paint. But expressing how that makes sense is quite difficult. Is it in an innocence? Is it in a mark? Is it in a certain colour? Is it in contrast? I think it's in all of that, but, as you say, there is also a classical idea of beauty that I very much appreciate. Even when it comes to the graphic and quite sexualised pieces I first became known for, I think there is an inherent beauty to them – there is always something in there, like a deconstructed idealised version of beauty, or a comment on the transience of youth. I do think beauty is intangible, and these commonalities and things that I'm interested in are complex, yet they are also paradoxically kind of simple. That is perhaps the beauty of art, to be able to communicate things that it wouldn’t be possible to express in any other way.

Do you have very specific intentions when facing a blank canvas? What do you think about the rise of generative digital art?

I have always felt that I’m just a conduit when making work – often people can look at a painting and get something from it that I had never consciously intended or seen, and I suppose that is the experiential element of the process that I enjoy most. There has always been a digital element to my painting, because from the get-go I was using the screen to find images – but, of course, back then it was just about using the internet to source imagery rather than utilising the possibilities of new platforms or technologies. It’s very different now. I’m a private person, and there is a real overtness in being open about everything on social media now, which, in terms of art-making, seems quite strange. I can't think of anything worse than to be putting work up on Instagram while it is in process, or while studying art. It must be a very odd experience to have that immediate judgement, and to be almost manoeuvred by the responses. It’s a different kind of mentality.